The Rebel: Margaret Tait | Wilma

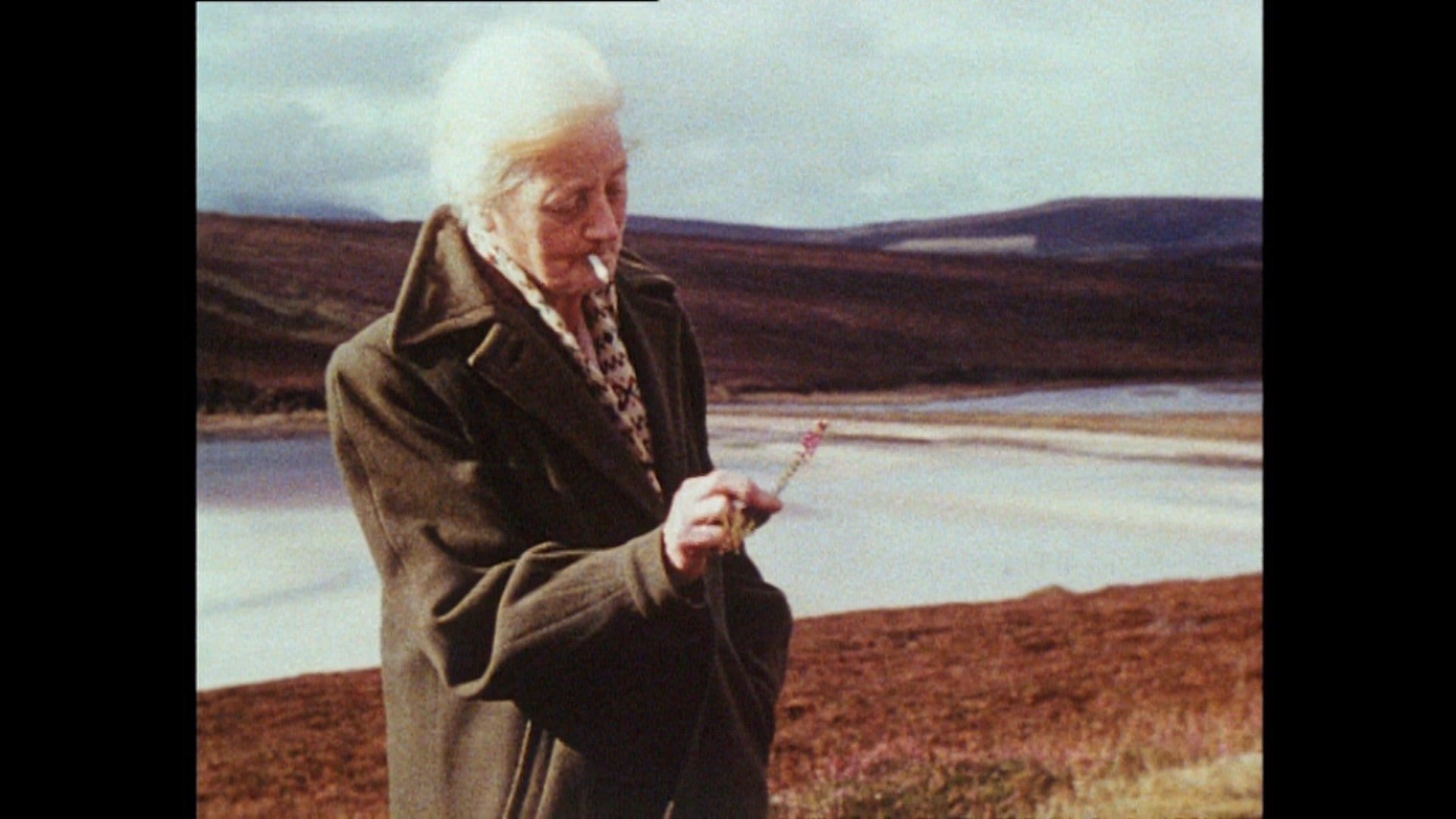

Still from Portrait of Ga, 1952. Courtesy of the Margaret Tait estate and LUX

A version of this piece first appeared in Wilma (active 2018-2019)

2018 is the centenary of Scottish filmmaker and poet Margaret Tait’s birth. BFI Southbank marks the occasion with a season of her work and as part of the celebration we take a closer look at Tait’s unique legacy.

Tait was born in 1918 on Orkney. Although she led a peripatetic lifestyle, serving as a doctor during World War Two and later studying filmmaking at Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, the island would prove to be her enduring muse. On her return from Italy in the 1950s, she moved to Edinburgh where she set up her film studio; Ancona Films on Rose Street. She eventually returned to Orkney in the 1960s and over the following decades continued to make films and write prolifically. Tait published three volumes of poetry and prose in her lifetime; Origins & Elements (1959), The Hen and the Bees (1960) and Subjects and Sequences (1960) which drew inspiration from her background and interest in science.

As a filmmaker and artist, Tait’s work continues to resist categorisation. Her intimate style sidesteps traditional narratives in favour of beautifully-lensed meditations of the small and often forgotten moments of everyday life. Her work runs contrary to conventional movements in cinema of that time, with influences more literary than cinematic. Tait was heavily inspired by Emily Dickinson, Ezra Pound and Federico Garcia Lorca. In 1964, she made a portrait film of the poet Hugh Macdiarmid, HUGH MACDIARMID: A Portrait. In 9 minutes, the film tenderly encapsulates the personality of its subject, as MacDiarmid recites poetry and responds to Tait’s interpretation of his work.

Working on 16mm with her trusted Bolex camera, these ‘film poems’ occasionally include snippets of Tait’s poetry appearing as a voiceover. In Portrait of Ga (1952), Tait follows her mother, known as ‘Ga’ by her grandchildren, around the ‘windy Orkney islands’ as she walks, smokes cigarettes, eats sweets and collects flowers. At just over four minutes long, the film is bewitching in its simplicity and captures her mother’s vibrant personality, suspended in time. One particular scene focusses on her mother’s hands as they unwrap a boiled sweet, her wrinkled hands carefully crinkling the foil. A mundane action acquires poignancy under Tait’s attentive and loving gaze.

In Land Makar; Tait focusses her attention on an Orkney croft; her camera bearing witness to the human labour involved in growing crops and raising livestock. Filmed over several seasons, the crofter Mary Graham Sinclair brings an immediacy and warmth to the screen with her lively presence. Tait constantly explored new ways of engaging with her environment through the eye of the camera but also with the medium of film itself. She experimented painting directly onto film as seen in Calypso (1956): a vibrant study of movement and colour accompanied by authentic calypso music. In Painted Eightsome (1970) she paints eights of figures, antlers and tartans moving in time to the lively music of the Orkney Strathspey and Reel Society. The result feels like an interlude between thought and feeling.

“A mundane action acquires poignancy under Tait’s attentive and loving gaze.”

Tait directed only one feature film in her lifetime. Blue Black Permanent (1992) is a multi-layered narrative spanning a family of three generations on Orkney. Set in Tait’s hometown of Kirkwall, the film captures the rich inner life of its protagonists Barbara and Greta, who appear to be loose representations of Tait herself with their histories and passions merging in places with the artist’s own biography. Like Tait, Greta is torn between her domestic life and the inner creative life she longs so much to nurture.

Tait was fiercely independent and carved her own path in the film industry from her home in Orkney, far from the British film establishment. While Tait’s work coincided with the social realism movement in British cinema that focused on domestic, working class life; Tait’s contributions took on a more abstract sensibility. Set apart from her contemporaries, Tait’s genre fluidity and refusal to be labelled as filmmaker or artist meant Tait struggled to find support and funding.

During her lifetime, Tait’s work found favour abroad rather than at home with many critics drawing parallels with experimental filmmakers like Stan Brakhage and Maya Deren. Today, Tait is celebrated as one of the first female filmmakers in Scotland: her body of work recognised as an integral part of the country’s rich documentary tradition. Resolutely dedicated to her vision and prolific in her output to the very end, Tait produced 32 short films and with the exception of three, these were entirely self-funded.

Tait died in 1999 but her legacy lives on with much of her film archive held at the National Library of Scotland Moving Image Archive where her film poems can be seen by a new generation. For Tait, Orkney was not simply the small island she grew up on but an opportunity to examine the bounty of inspiration that flourishes in a place if one lingers long enough to watch it unfold.

Margaret Tait 100 is a year-long celebration of Tait’s work, in partnership with LUX Scotland, University of Stirling, and Pier Arts Centre, Orkney.